Make a statement with these high jewellery brooches

In honour of Madeleine Albright (1937 – 2022), who as US secretary of state frequently communicated her diplomatic intentions through a vast collection of brooches, we revisit an exquisite array of high jewellery pieces, first featured in Wallpaper’s October 2016 issue

Bulgari: The rectangular form of baguette-cut diamonds presents the gemsetter with a graphic tool, here adding depth to Bulgari’s white-diamond spirals and figurative definition to the ‘Serpenti’ brooch. Pictured, ‘The Magnificent Inspirations’ brooch (far left) in platinum with 60 round brilliant- (29.28ct) and tapered baguette-cut diamonds (7.02ct); the ‘Magnificent Inspirations Serpenti’ brooch (top) in white gold, with baguette- and tapered cut diamonds (6.92ct) and standout square- (2.01ct) and pear-cut diamonds, both by Bulgari.

De Beers: Baguette-cut diamond spokes form an abstract framework for De Beers’ diamond medallion. Pictured, brooch (bottom), detachable from the ‘Elizabeth Tower’ necklace, in white gold with 356 diamonds in four cuts – round, princess, baguette, pear – including the central round brilliant (3.03ct), by De Beers. Jacket, by Christian Wijnants.

Fashion: Jason Hughes. Watches & Jewellery director: Caragh McKay

The brooch as a jewel form has been somewhat undervalued in recent years. Commonly perceived as being out of sync with contemporary tastes, its often-baroque nature is often dismissed as being too narrative rich for simpler, cleaner tastes. But brooches are best viewed beyond fashion, in high jewellery terms, as three-dimensional sculptures that push expectations of the materials used. Unlike like rings or earrings, they are not restricted to a particular part of the body – brooches allow designers and makers broader artistic scope. Toying with scale, perspective and traditional notions, as our story (first published in Wallpaper’s October 2016 issue) shows, when designed and crafted at this level, the brooch can become a powerful art object in its own right.

Harry Winston: A spray of knife-set diamonds forms this meditation on two classic stone cuts – round- brilliant and pear. ‘Cascading Drop’ brooch in platinum with 169 round brilliant and 16 pear-shape diamonds (totalling 35.21ct), by Harry Winston. Dress, by Boss

Tiffany & Co: Legendary Tiffany jewellery designer Jean Schlumberger was drawn to the irregularities of natural forms, slight ugliness being a necessary

foil for an overtly romantic outcome. In turn, their intricate twists and turns allow gemsetters to display their own talents, as with

this re-edition of a 1950s Schlumberger brooch. ‘Jean Schlumberger Guadeloupe’ brooch (top), from the 2016 Masterpieces collection, in 18ct gold with 79 round pink spinels (11.21ct) and eight round spessartites (1.37ct), by Tiffany & Co.

Cindy Chao: The freedom to express

her sculptor’s instincts

in various jewelled forms

makes brooches the standout design in each Chao collection. Her

fine art approach manifests

in the ‘Rose Petals’ brooch, created in four parts. ‘Rose Petals’ brooch in silver and 18ct yellow gold (only two pieces shown), with central oval-cut diamonds (1.51ct and 2.05ct) and various cuts totalling 48.12ct, by Cindy Chao. Jacket, by Cédric Charlier

Chaumet: a pear-cut exclamation point highlights the vivacious character of Chaumet’s summer wheatsheaf. Its elegant nature is distinguished by exquisite craftsmanship. La Nature de Chaumet ‘Offrandes d’Été’ brooch (on collar) in white gold and brilliant-cut diamonds, with 2.21ct pear drop.

Dior Joaillerie: Interior details from the Château de Versailles are translated into tangled, sculpted jewels shimmering with sizeable velvet-hued stones. Designing the pieces as if viewed by candlelight led designer Victoire de Castellane to consider alternative materials, such as blackened silver.

Dior à Versailles ‘Salon de Diane’ brooch (left) in white, yellow and pink gold, and darkened silver, with 154 round- (6.21ct) and three pear-cut diamonds (1.51ct; 1.01ct; 0.70ct) and pear-cut emerald (2.18ct), by Dior Joaillerie.

Piaget: the watchmaker-jeweller’s distinct house engraving techniques add a lush, organic feel to this fan of red-gold palm leaves, pinched artfully together with a 2.51ct green tourmaline baguette.

Brooch (right), detachable from The Sunny Side of Life ‘Golden Palm’ necklace, in 18ct red gold with green tourmaline baguette (2.51ct), and 60 white diamonds (15ct), by Piaget. Cape; coat (worn underneath), both by Agnona

Suzanne Syz: Her pop art background and craftsman’s approach are

the fundamentals in Suzanne Syz’s postmodern creations,

as this grotesque mélange

of rare materials and cartoon-

like references reveals. ‘Kermit on a Lilypad’ brooch (top) in yellow gold with chrysoprase, spessartite garnets (38.03ct), tsavorites (45.89ct), cabochon rubies (0.66ct) and diamonds (0.29ct), by Suzanne Syz.

Chanel Fine Jewellery: The ancient symbolism

of wheat inspired Chanel’s

Les Blés de Chanel collection, which is why

it is quietly, beautifully rooted in Classicism. Moisson Ensoleillée’

brooch (right) in 18ct white and yellow gold, with 19 marquise-, seven pear- and 168 brilliant-cut diamonds, 209 brilliant-cut yellow sapphires and one central octagonal-cut African yellow sapphire (10.22ct),

by Chanel. Jacket, by Victoria Beckham

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Louis Vuitton: the new era of brooch designs reflects 19th-century tastes, where the highly precious nature of materials did not inhibit scale, nor restrict a brooch to a particular area of the body, as in Louis Vuitton’s ‘lace’ garland of diamonds. ‘Diamonds’ brooch (top) in white gold with diamonds (10.74ct), from the Dentelle de Monogram collection, by Louis Vuitton.

Boucheron: Designer Claire Choisne’s plush peacock plume of diamonds is crafted in two pieces, designed to create the illusion of bird feathers transforming into a flock. ‘Plume de Paon’ brooch (below) in 18ct white gold with one pear-cut diamond (0.08ct) and 499 round brilliants (3.33ct), by Boucheron

Top, £395, by Pringle of Scotland. Skirt, by Marni

Amrapali: Polished perfection is not typical of the traditional Indian fine jewellery aesthetic, where the

visceral power of stones

is paramount. This white-gold wreath design of

non-uniform pearls and tumbled 45.64ct rubellite tourmaline underlines

the organic Indian style. Brooch in 14ct gold and sterling silver, with

128 round brilliant-cut diamonds (0.76ct);

oval-cut emerald (1.15ct) and 14 South Sea pearls (9.46ct), with central tumbled rubellite tourmaline briolette (45.64ct), by Amrapali.

Cartier: The French jewellery house’s creative links to India

and its particular jewellery design codes are reflected

in the compelling nature

of this carved rubellite. ‘Caresse d’Orchidées’ brooch of rubellite tourmaline (414.45ct),

with one diamond pear- (0.73ct) and 186 round brilliant-cut diamonds (2.08ct), by Cartier. Jacket, by MaxMara

Graff: Gradating tiers of marquise-cut diamonds add a natural sense of movement to Graff’s magnificent ‘Bird of Paradise’ and its everlasting delivery of a 2.02ct pear drop. Pavéd brilliants add volume and texture to its narrative form. ‘Bird of Paradise’ brooch in 350 diamonds (27ct), including pavé set, pear- and marquise-cut, with central 2.02ct pear, by Graff. Top, by Bally

Caragh McKay is a contributing editor at Wallpaper* and was watches & jewellery director at the magazine between 2011 and 2019. Caragh’s current remit is cross-cultural and her recent stories include the curious tale of how Muhammad Ali met his poetic match in Robert Burns and how a Martin Scorsese Martin film revived a forgotten Osage art.

-

Head out to new frontiers in the pocket-sized Project Safari off-road supercar

Head out to new frontiers in the pocket-sized Project Safari off-road supercarProject Safari is the first venture from Get Lost Automotive and represents a radical reworking of the original 1990s-era Lotus Elise

By Jonathan Bell

-

Kapwani Kiwanga transforms Kvadrat’s Milan showroom with a prismatic textile made from ocean waste

Kapwani Kiwanga transforms Kvadrat’s Milan showroom with a prismatic textile made from ocean wasteThe Canada-born artist draws on iridescence in nature to create a dual-toned textile made from ocean-bound plastic

By Ali Morris

-

This new Vondom outdoor furniture is a breath of fresh air

This new Vondom outdoor furniture is a breath of fresh airDesigned by architect Jean-Marie Massaud, the ‘Pasadena’ collection takes elegance and comfort outdoors

By Simon Mills

-

Jewelled watches: five iconic designs get a glittering makeover

Jewelled watches: five iconic designs get a glittering makeoverFrom the Rolex Daytona to the Patek Philippe Aquanaut, 2024 is a dazzling year for jewelled verions of watch design classics

By Caragh McKay

-

Cartier celebrates the art of craft in Venice

Cartier celebrates the art of craft in VeniceCartier has created a unique piece for Homo Faber 2022 that is at once jewellery and objet d’art

By Hannah Silver

-

Cartier high jewellery watches encompass playful design codes

Cartier high jewellery watches encompass playful design codesThe Indomptables de Cartier watch collection draws on Cartier’s history of incorporating animals into iconic designs

By Hannah Silver

-

Cartier wins Best Glove Affair: Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

Cartier wins Best Glove Affair: Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022The Cartier Clash [Un]Limited mitten watch, by Cartier, is crafted from supple rose gold mesh and set with nearly 1,600 diamonds

By Hannah Silver

-

Watches for men nod to sporty design codes

Watches for men nod to sporty design codesYou’ll see why we’re big on these sporty watches for men

By Hannah Silver

-

The American Museum of Natural History celebrates animal jewellery

The American Museum of Natural History celebrates animal jewelleryA new exhibition, Beautiful Creatures, marks the opening of the new Allison and Roberto Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals

By Hannah Silver

-

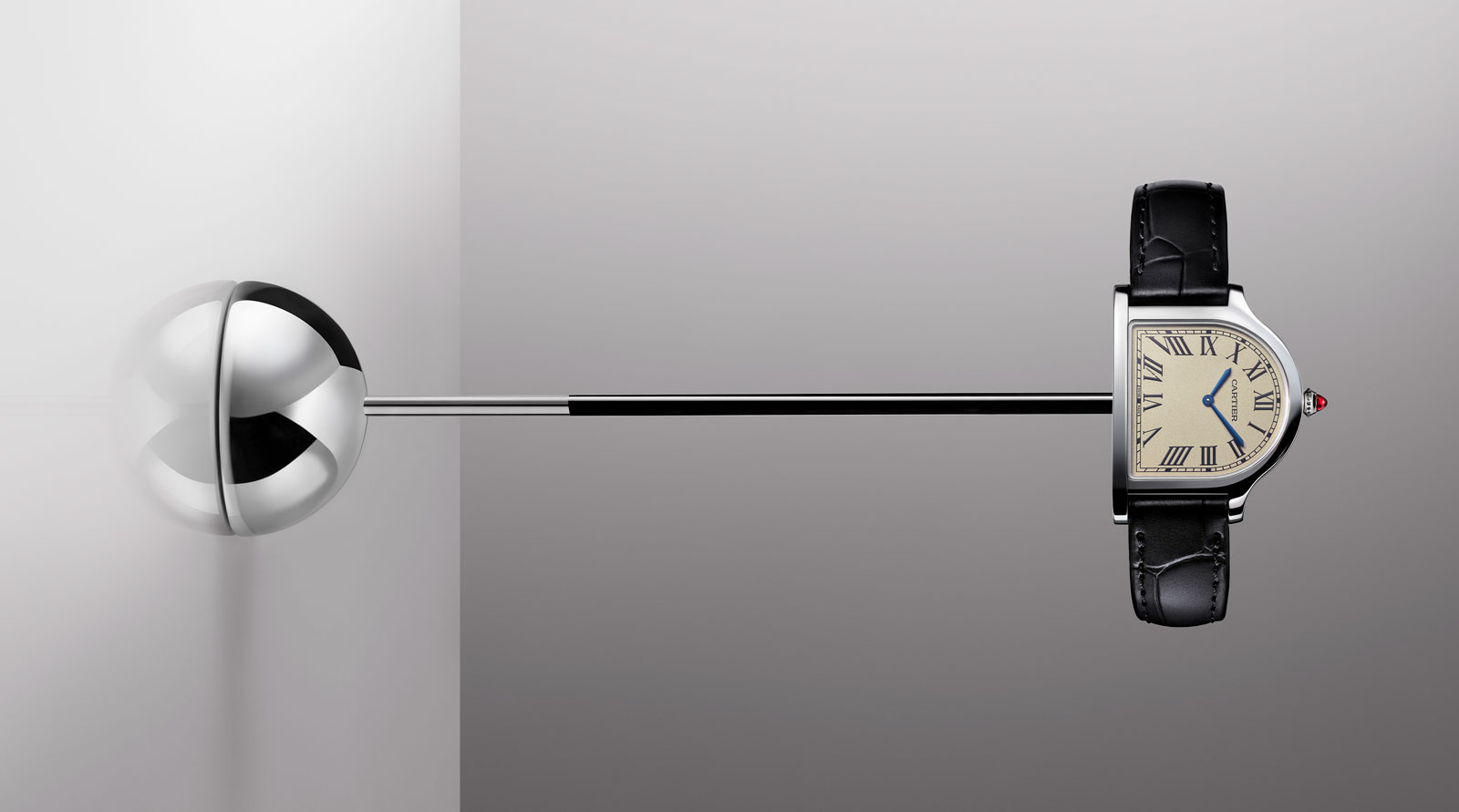

Cartier’s new watch pays tribute to the original 1920s bell-shaped design

Cartier’s new watch pays tribute to the original 1920s bell-shaped designThe Cartier Privé Cloche de Cartier has been unveiled as one of Cartier’s key watch launches of the year

By Hannah Silver

-

Cartier pays homage to its most iconic designs

Cartier pays homage to its most iconic designsThe Cartier Santos, Tank, Trinity, Love, Juste Un Clou, Panthère and Ballon Bleu jewellery and watch collections have been brought together for the first time

By Hannah Silver