Omega timekeeping: Olympic-standard timing over the years

This article originally featured in the June 2012 issue of Wallpaper* (W*159)

In a business where a fraction of a moment; a tenth or a thousandth of a second, can make or break careers, lives, people – in sports watches, timing is everything. Since the first modern Olympic Games, in Athens in 1896, time measurement has been the pivot around which the event turns. It’s a serious job: serious timekeepers need to do it.

A few watch brands have taken on the task in the hundred-odd years of the event’s history. Swiss motorsports timer Heuer, (it acquired the TAG prefix in 1985) was a natural partner in the 1920s, while Seiko had its Olympics heyday in the 1990s. But it is the Biel-based brand Omega that has had the most consistent link, and London 2012 marks its 25th outing as Official Timekeeper.

It’s no mere brand-endorsement exercise, either: the pursuit of ever more precise timing is what makes the watch world tick but the Official Timekeeper is under scrutiny to develop equipment that is not just up to the job but that is better at it. Hence, affiliated watch companies have always poured huge resources into sports-timing technology.

And, because Omega has presided over a century of change, when stopwatch holders at the touchline reluctantly gave way to electronic timers then digital methods, the company’s role as a technology pioneer is pretty impressive. Its engineers have spent decades developing kit that is not only elegantly designed – so as not to impede audience views of athletes crossing the finishing lines – but that performs and concurs with the demands of athletes, officials and the millions of people who watch the Games on TV.

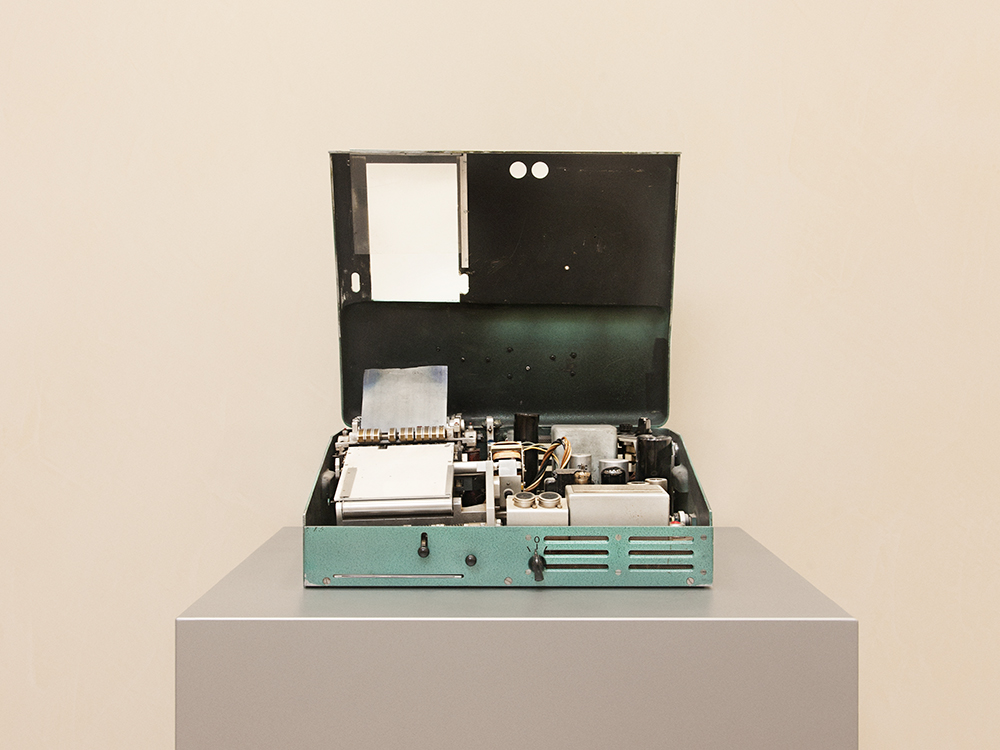

The Omega Time Recorder OTR1, 1952, used by timekeeping sports where there are no problems of competitors’ finish order, or in disciplines with staggered finishes.

Take the Omegascope, which launched in 1961. By enabling live running times to be relayed on television for the first time, it directly engaged audiences, enhancing viewer experience, making broadcasting history while it was at it.

Even during war time Omega’s engineers were busy developing a real Game-changer: the Racend Omega Timer, a camera ‘that films time’. It made its debut at the Olympic Games in London, in 1948, where it was nicknamed the ‘Magic Eye’. Prior to that, records were set via human eye determining which athlete first crossed the rope, then pushing the button on a stopwatch. As final speeds are often just seconds apart and human response is not an accurate measure, naming the winner was, essentially, a task beyond human capability.

‘Finding a system that could stop a person crossing the line was a big development,’ says 75-year-old Peter Hürzeler, the leading sports-timing engineer and member of the Omega Timing board, referring to the fact that film could be slowed down and properly examined. ‘Though, even in 1948, hand-stopping was still used as official time – they only resorted to photo-finish if they weren’t sure.’ However, it soon became clear that photographic evidence was as close to precision timing as the Games had come and, by Mexico City 1968, electronic timekeeping was the official standard. Stressing the importance of equipment development, Hürzeler relays this story: ‘Lee Evans became the first man to break 44 seconds, winning the 400 metres in the 1968 Games at 43.86 seconds. That world record was only beaten 20 years later in Zurich by Butch Reynolds, who completed the race in 43.29 seconds.’

Hürzeler is a man who not only knows all there is to know about Olympic timekeeping but who is also on first-name terms with those sporting greats whose names we’ve all grown up with, because timekeepers, he says, are often the first people an athlete wants to see after a race, eager to dissect their performance. Hürzeler earned his place in sporting history as the engineer who, in 1972, designed a new version of the Photosprint, an updated version of 1948’s Racine.

‘Previous photo-finish machines took anything up to half and hour to relay actual times,’ he points out. ‘Machines had to be dismounted and taken to a dark room, where multi reels of film were unlocked and processed before they could be brought into the control room.’ The aim of the Photosprint was to speed up the film processing so that the correct results could be delivered to the control room, the athletes – and the world – faster. Hürzeler worked with Kodak to produce a lock-free film that did just that.

Naturally, Olympics timekeeping is computer-based now but Omega continues to accelerate change, propelling the future of sporting performance along with it. At the start of this year, Hürzeler could be found conferring with practising swimmers at Zaha Hadid’s Aquatics centre in East London about whether improvements in Omega’s touch-pad technology – a system that responds to a swimmer’s touch but not the movement of the water – would pass muster.

The jury was still out but Hürzeler brimmed with all the optimism of a young product designer: ‘If you are a pessimist you’ll have a lot of problems; you’ll find 200 reasons why something won’t work. But you have to be a little bit optimistic: that’s the solution to being able to create something new. Athletes believe in the system, even though they have no idea how it works.’

The Racend Omega Timer, 1952, used at the Olympic Games in Helsinki (1952), Melbourne (1956) and Rome (1960)

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Omega website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Caragh McKay is a contributing editor at Wallpaper* and was watches & jewellery director at the magazine between 2011 and 2019. Caragh’s current remit is cross-cultural and her recent stories include the curious tale of how Muhammad Ali met his poetic match in Robert Burns and how a Martin Scorsese Martin film revived a forgotten Osage art.

-

Sabine Marcelis has revisited her Ikea lamp and it’s a colourful marvel

Sabine Marcelis has revisited her Ikea lamp and it’s a colourful marvelSabine Marcelis’ ‘Varmblixt’ lamp for Ikea returns in a new colourful, high-tech guise

-

Is the Waldorf Astoria New York the ‘greatest of them all’? Here’s our review

Is the Waldorf Astoria New York the ‘greatest of them all’? Here’s our reviewAfter a multi-billion-dollar overhaul, New York’s legendary grand dame is back in business

-

Colleen Allen’s poetic womenswear is made for the modern-day witch

Colleen Allen’s poetic womenswear is made for the modern-day witchAllen is one of New York’s brightest young fashion stars. As part of Wallpaper’s Uprising column, Orla Brennan meets the American designer to talk femininity, witchcraft and the transformative experience of dressing up

-

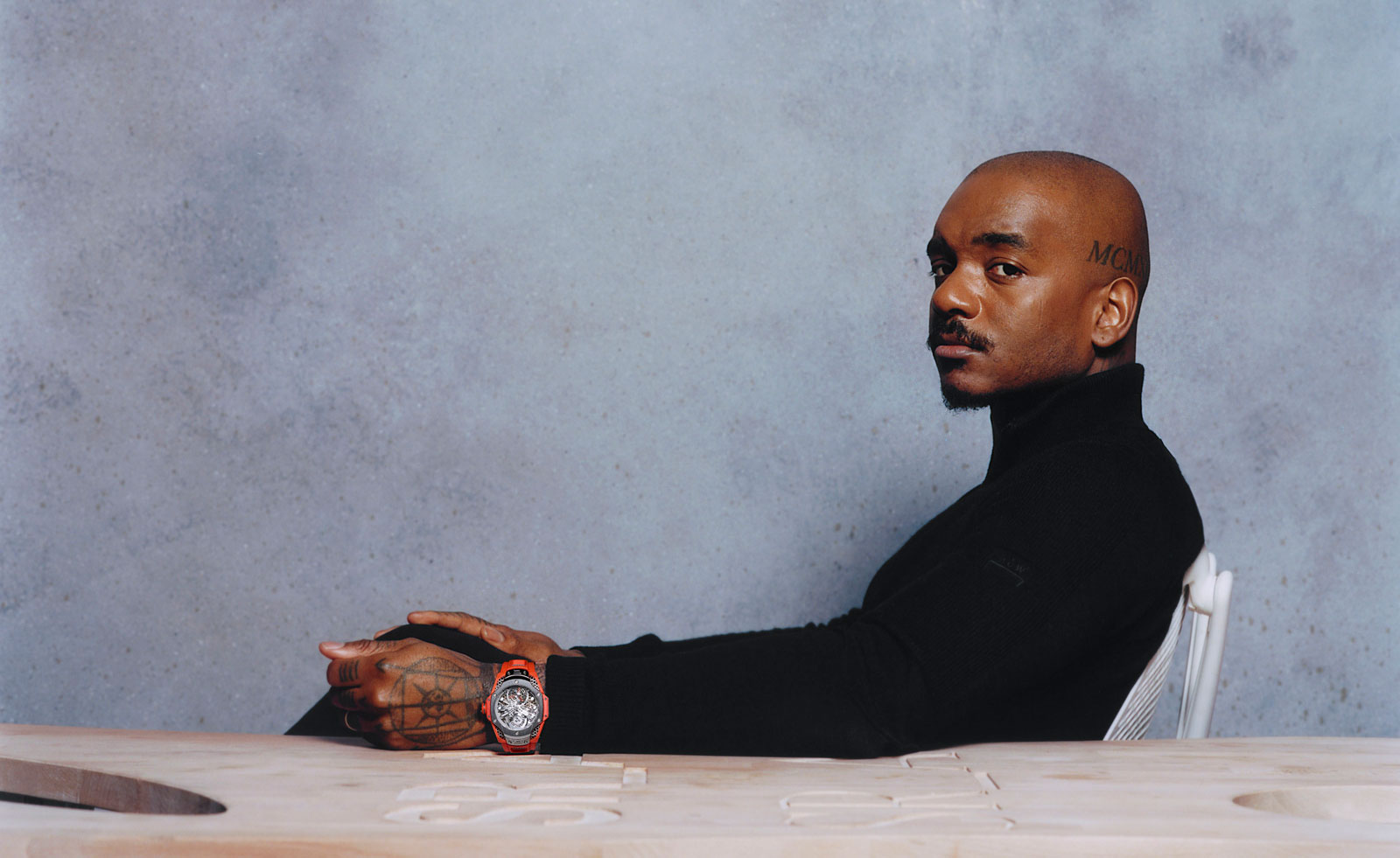

Samuel Ross unveils his Hublot Big Bang watch design

Samuel Ross unveils his Hublot Big Bang watch designSamuel Ross brings a polished titanium case and orange rubber strap to the Hublot Big Bang watch

-

Playful design meets chic heritage in the Hermès Kelly watch

Playful design meets chic heritage in the Hermès Kelly watchThe new Kelly watch from Hermès rethinks the original 1975 timepiece

-

Discover the tonal new hues of the classic Nomos Club Campus watch

Discover the tonal new hues of the classic Nomos Club Campus watchThe Nomos classic wristwatch Club Campus now comes in two new collegiate colours. The perfect graduation gift from the Glashütte manufacture

-

Bulgari unveils the thinnest mechanical watch in the world

Bulgari unveils the thinnest mechanical watch in the worldThe new Bulgari Octo Finissimo Ultra watch is a record-breaking feat of engineering

-

Breitling and Triumph unite on a racy new watch and motorcycle

Breitling and Triumph unite on a racy new watch and motorcycle1960s design codes are infused with a contemporary edge in the collaboration between Breitling and Triumph

-

Gerald Genta’s mischievous Mickey Mouse watch design is rethought for a new era

Gerald Genta’s mischievous Mickey Mouse watch design is rethought for a new eraThe Gerald Genta Retrograde with Smiling Disney Mickey Mouse watch pays tribute to Genta’s humorous design codes

-

Shinola honours Georgia O’Keeffe with a new watch

Shinola honours Georgia O’Keeffe with a new watchShinola Birdy watch stays faithful to the minimalist codes of Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting, My Last Door

-

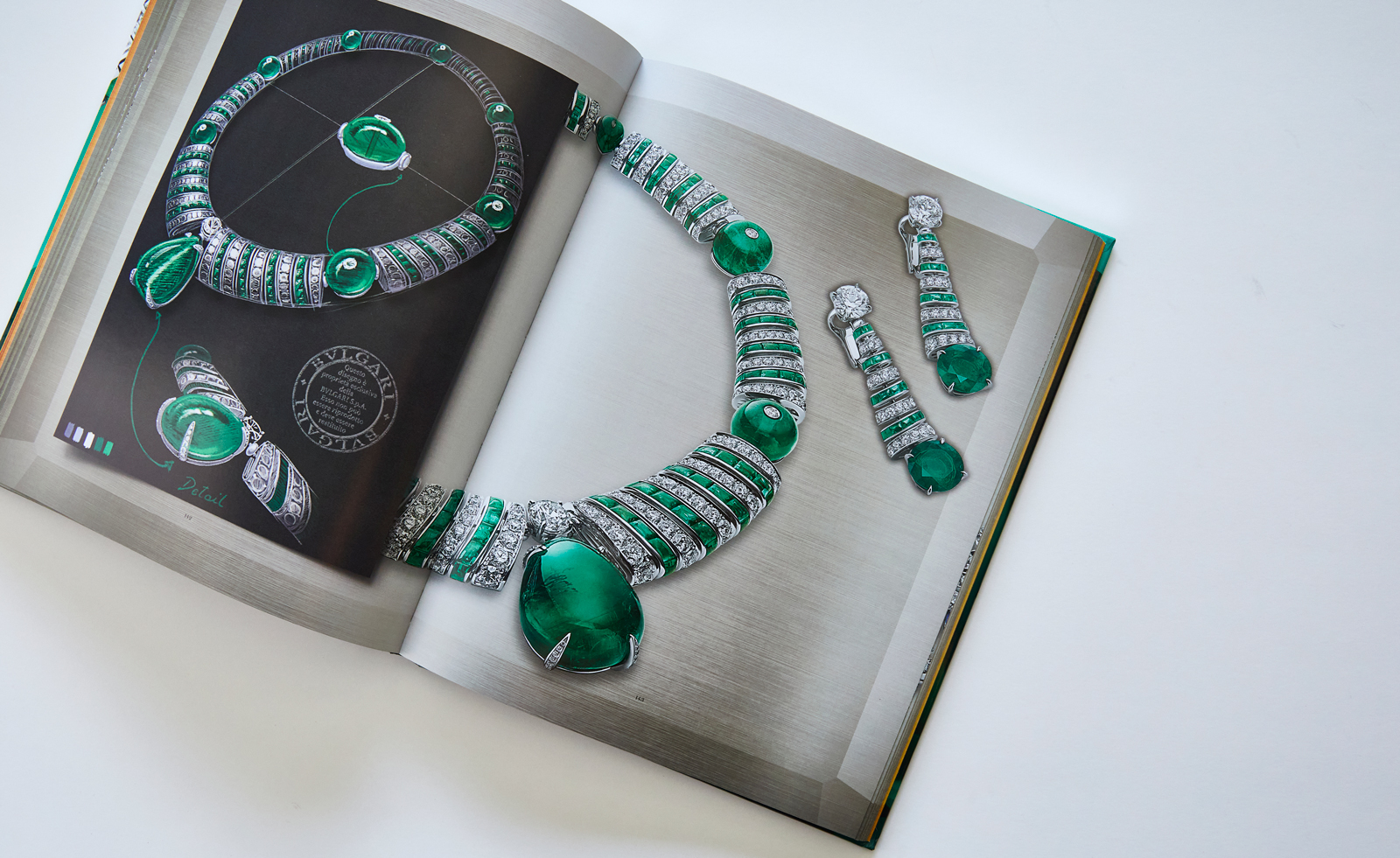

Bulgari’s new book celebrates women and high jewellery

Bulgari’s new book celebrates women and high jewelleryBulgari Magnifica: The Power Women Hold, published by Rizzoli New York, takes a closer look at the female muses who inspired the spectacular Magnifica high jewellery collection