Deep thinker: Seiko engineer Ikuo Tokunaga’s subaqueous solutions

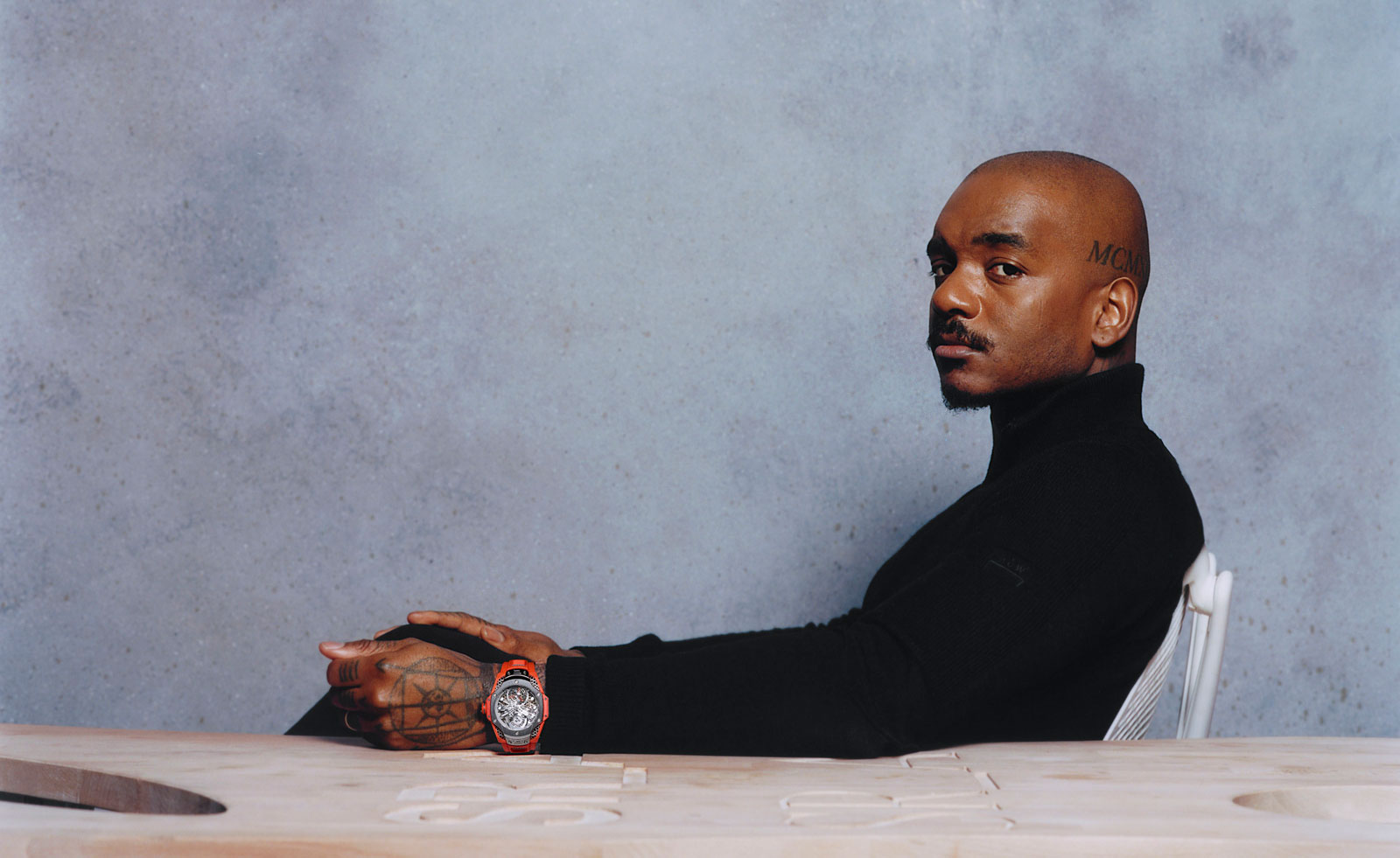

Left, Ikuo Tokunaga, photographed at the Seiko Museum, Sumida in August 2017. Tokunaga wears, from left to right, a Grand Seiko Spring Drive Chronograph and his own customised Seiko Professional Diver’s design, based on several post-1975 versions of the so-called ‘Tuna’ models. Right, the Prospex Automatic Divers’ watch (£799) and the Prospex Diver limited edition (£3,750); both available at Seiko’s new London flagship boutique.

Whether it’s the ‘Orange Monster’, ‘Tuna Can’ or ‘Sumo’, the release of a new Seiko diver’s watch sparks frenzied debate (and nickname invention) on online watch forums. This year, there is plenty to talk about as the Japanese watchmaker launches a replica edition of its first-ever mechanical diver’s design, along with two new superior-tech versions, due in stores this month.

Seiko entered the performance watch arena in 1965. Buoyed by its association with the Olympic Games, as official timekeeper for Tokyo 1964, it had begun to consider the new era of gadget-hungry consumers. Its first diver’s effort was well received, the clean, wide hands and dial markings presenting a contemporary Japanese take on an established Western template. Water-resistant to 150m, its high legibility and tough construction also led to the watch being adopted as a key tool for the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition in 1966.

But it was an altogether more personal challenge – and the dogged determination of an independent engineer, Ikuo Tokunaga – that led to the launch of its Prospex Professional Diver’s series in 1975. The watch featured a number of technical firsts and established Seiko as a serious player in professional instruments.

‘Just before I started working with Seiko in the late 1960s, a letter from a professional diver had arrived at the company’s head office,’ recalls the now-retired Tokunaga, who worked with Seiko for 35 years and is a revered figure in the business today. ‘He explained that no diver’s watches, including imported ones, were of use to him in his field as he worked in the oil and gas industry using a saturation diving technique, featuring a mix of helium and oxygen. We visited his team and asked them about the problems they were having.’

Working at 350m depths in pitch-black, freezing conditions was among them. But the most significant problem was not the water resistance under high pressure that other diver’s watches were designed to combat, but the lack of resistance to helium gas, particles so small they penetrated the gasket.

Tokunaga was not a watchmaker. Rather, his focus was the behaviour of material structures. He started to experiment with titanium. ‘Compared to stainless steel, titanium is an ideal material for diver’s watches because of its corrosion resistance, intensity and lightness,’ he says. ‘However, as this was the 1970s, we had to develop new technology. Pressure-testing equipment was not hard, but the device to test the helium gas penetration was very challenging.’ His solution was a single-construction lightweight case and an L-profile gasket that enabled an air- (and helium-) tight fit of the glass to the dial. In 1975, Seiko launched a completely new type of diver’s watch, affording unprecedented gas-tightness, for professional use.

The team had notched up 23 horological firsts in the process, including the unique accordion polyurethane strap, designed to move with the expansion and contraction of a diver’s wrist as he reached new depths. Now a classic Seiko diver’s watch motif, it was devised by another of the brand’s lauded design associates, Taro Tanaka, who was inspired by the folding camera he used. Tanaka also created the Professional Diver’s outer case construction, aka the ‘Tuna Can’.

Seiko has a healthy tradition of partnering with independent designers. In the late 1890s, its founder Kintaro Hattori met 28-year-old engineer Tsuruhiko Yoshikawa and they started producing their own clock, the ‘Bonbon’, as an alternative to popular Western imports. By 1924 it had paved the way for Hattori to capitalise on the Japanese predilection for precision (seiko) and establish the world’s first Japanese clock and watch manufacturing business.

As originally featured in the October 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*223)

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Seiko website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Caragh McKay is a contributing editor at Wallpaper* and was watches & jewellery director at the magazine between 2011 and 2019. Caragh’s current remit is cross-cultural and her recent stories include the curious tale of how Muhammad Ali met his poetic match in Robert Burns and how a Martin Scorsese Martin film revived a forgotten Osage art.

-

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campus

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campusThe Lighthouse, a Los Angeles office space by Warkentin Associates, brings together Bauhaus, brutalism and contemporary workspace design trends

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

Samuel Ross unveils his Hublot Big Bang watch design

Samuel Ross unveils his Hublot Big Bang watch designSamuel Ross brings a polished titanium case and orange rubber strap to the Hublot Big Bang watch

By Pei-Ru Keh

-

Playful design meets chic heritage in the Hermès Kelly watch

Playful design meets chic heritage in the Hermès Kelly watchThe new Kelly watch from Hermès rethinks the original 1975 timepiece

By Hannah Silver

-

Discover the tonal new hues of the classic Nomos Club Campus watch

Discover the tonal new hues of the classic Nomos Club Campus watchThe Nomos classic wristwatch Club Campus now comes in two new collegiate colours. The perfect graduation gift from the Glashütte manufacture

By Hannah Silver

-

Bulgari unveils the thinnest mechanical watch in the world

Bulgari unveils the thinnest mechanical watch in the worldThe new Bulgari Octo Finissimo Ultra watch is a record-breaking feat of engineering

By Hannah Silver

-

Breitling and Triumph unite on a racy new watch and motorcycle

Breitling and Triumph unite on a racy new watch and motorcycle1960s design codes are infused with a contemporary edge in the collaboration between Breitling and Triumph

By Hannah Silver

-

Gerald Genta’s mischievous Mickey Mouse watch design is rethought for a new era

Gerald Genta’s mischievous Mickey Mouse watch design is rethought for a new eraThe Gerald Genta Retrograde with Smiling Disney Mickey Mouse watch pays tribute to Genta’s humorous design codes

By Hannah Silver

-

Shinola honours Georgia O’Keeffe with a new watch

Shinola honours Georgia O’Keeffe with a new watchShinola Birdy watch stays faithful to the minimalist codes of Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting, My Last Door

By Hannah Silver

-

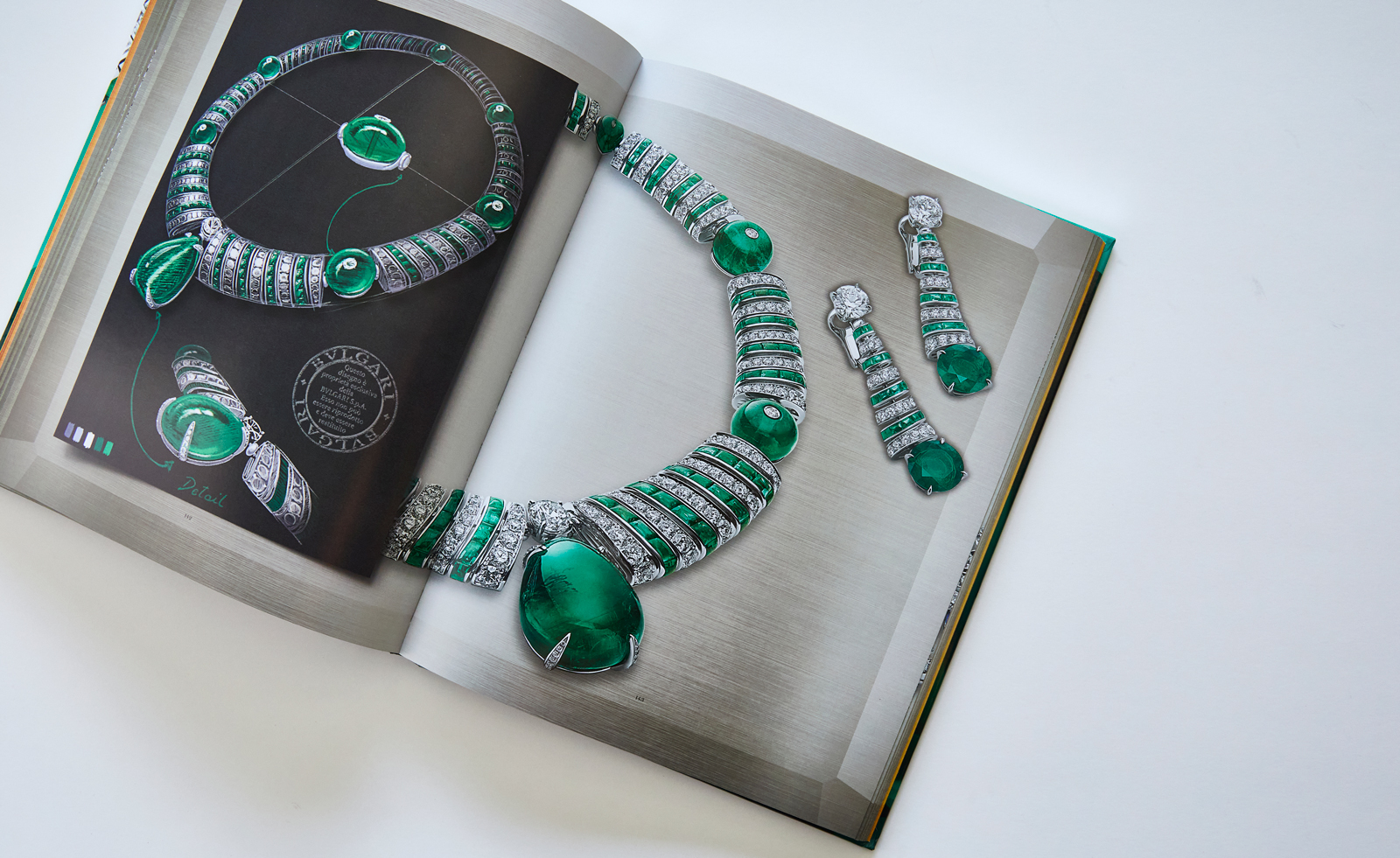

Bulgari’s new book celebrates women and high jewellery

Bulgari’s new book celebrates women and high jewelleryBulgari Magnifica: The Power Women Hold, published by Rizzoli New York, takes a closer look at the female muses who inspired the spectacular Magnifica high jewellery collection

By Hannah Silver