Once upon a time: Van Cleef & Arpels’ automaton tells a very human story

Nothing captures the uncanny wonder of mechanical craft quite like figurative automata. Hand-programmed to mimic not just human movement but often emotions too, these clockwork figures, popularized in 18th-century royal courts, are today mostly seen in museums. So an invitation to visit the automaton maker François Junod, in his studio in the Swiss mountain region of Vaud, is an intriguing one.

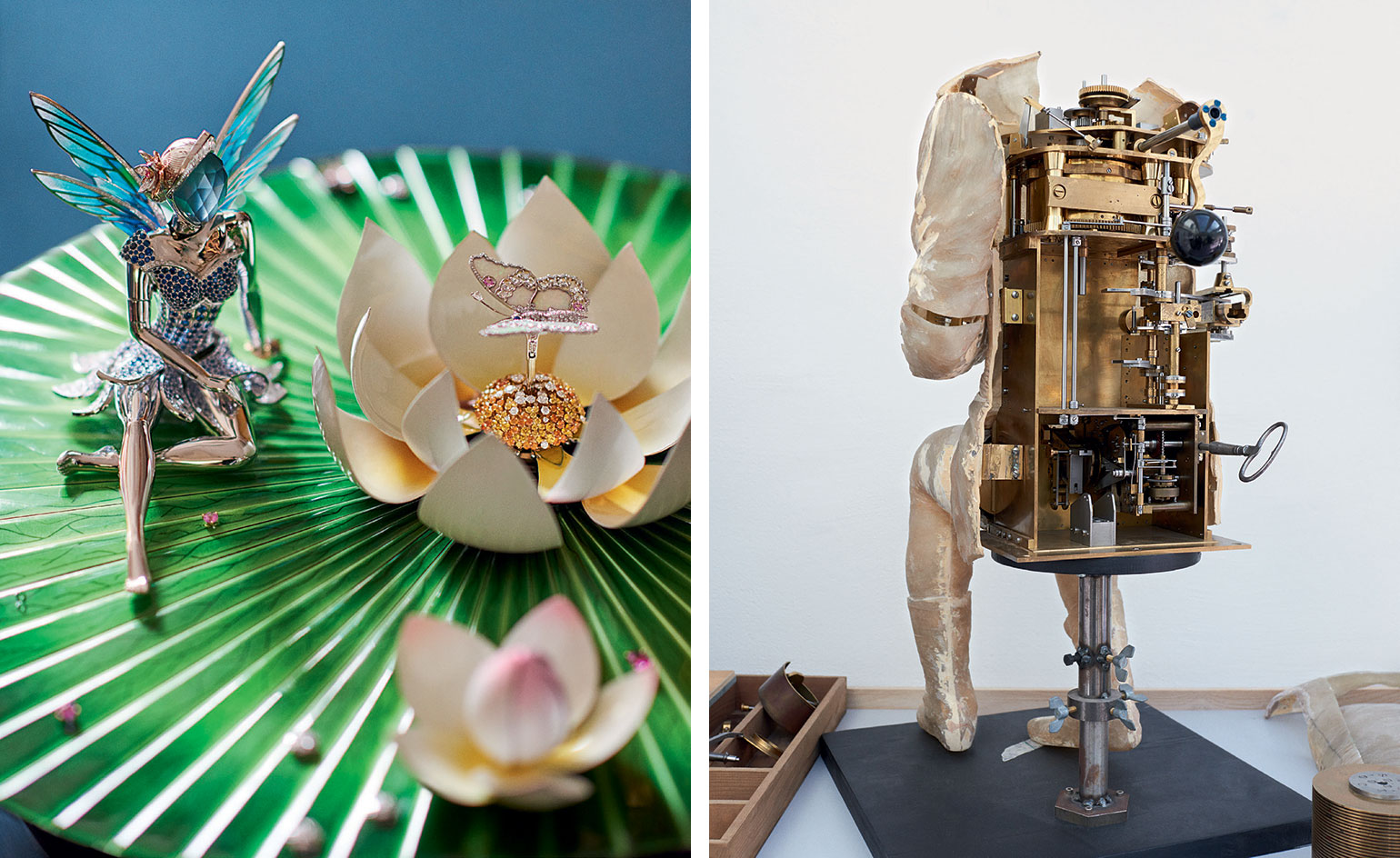

Bar a cult following in Japan, Junod is relatively unknown outside the core Swiss watch community (his skill is related to traditional horological engineering). He is one of just a handful of contemporary automata craftsmen. This year, his reputation as a master is being heightened further by a collaboration with Van Cleef & Arpels. Junod was one of 20 remarkable craft specialists invited to collaborate on a unique brief for the French jewellery house: the extraordinary Fée Ondine automaton. The sizeable enamelled table clock is designed to tell a fairytale. Junod created the automated aspects of the entire piece and gave life to its star turn – a lithe-limbed, white-gold fairy around whose lifelike movements the clock’s story magically unfolds.

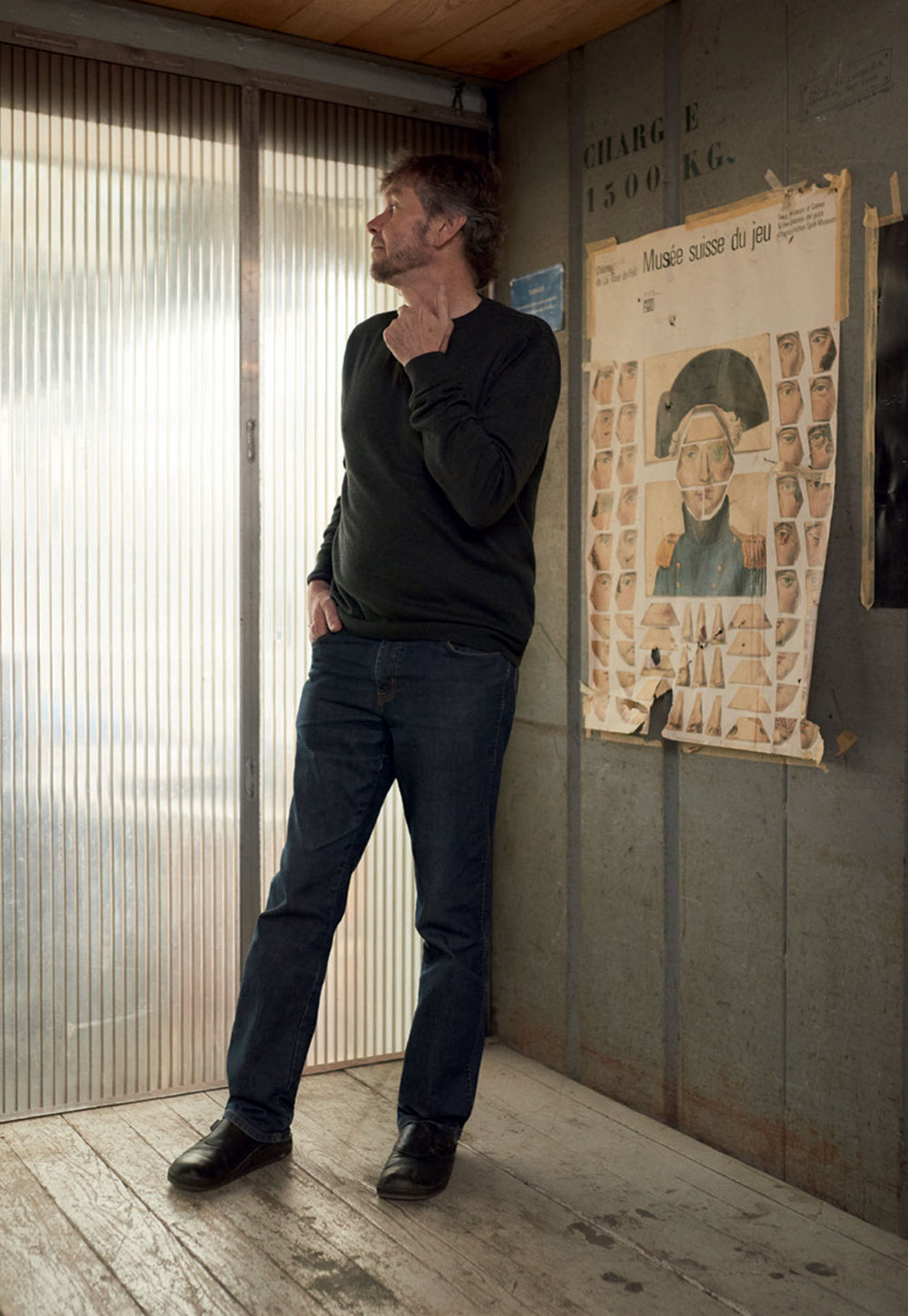

‘The difference between automata and robots is that automata have soft, organic movements,’ says Junod from his mountain-top studio. Crammed with motors, rotors, hammers, toy limbs, record players, cine cameras, chisels, jukeboxes and much, much more, his Sainte-Croix workshop is a film set waiting to happen. ‘The goal is to put life inside the automaton, to tell a story so that it’s not just a mechanism. That is dependent on the gear cams – the mechanical programming. To get a graceful movement, you have to have precision in the system and you have to regulate the speed. You don’t want the fairy’s wings to start fast then go slow, as she would look really sad.’

Judging by his workshop, Junod’s love for all things mechanical is all-encompassing. ‘I study old cameras to come up with solutions, because the regulator inside them is very subtle,’ he says, gesturing upwards to the row of analogue cameras and cine machines dangling from a jam-packed ceiling beam.

‘Automatons are magic,’ says Nicolas Bos, president and chief executive of Van Cleef & Arpels. ‘We tend to think of them still as products of the 18th century – tinny, dusty characters. On the other hand, contemporary ones strive to be modern, abstract, geometrical, but then the emotion is gone. We wanted a 20th-century evocation, a true character and environment, and that’s how we met François. We spent a lot of time discussing the scenario.’

Junod, who developed the clock’s complex mechanism, at his workshop

Enchantment for its own sake is a central theme of Van Cleef & Arpels’ narrative. Throughout its 110-year history, the house has also applied its materials expertise to the creation of rich interior art pieces, mostly with a functional purpose. Craft for craft’s sake, however, has never been the driver for Bos in his time at Van Cleef & Arpels. ‘Our mechanics always start with the stories, never the technique,’ he says. ‘If there is a butterfly or a bird, you want it to have its own life. You learn and rediscover techniques as you work. It’s almost a philosophy you can interpret, as in more surprise, more poetry, more three-dimensionality.’

The Fée Ondine automaton is a continuation of Van Cleef ’s ‘Extraordinary Objects’ series. The time is displayed by way of a tiny jewelled ladybird on the ebony veneer base that supports the animated fairytale above. In the tradition of automata control, the piece is also fitted with a giant key; when turned, it powers the meticulously programmed mechanics that bring the scene to life. As the leaves of a giant enameled lilypad ripple, the fairy awakens and gently moves her arm aside. Tilting her head, she looks on as if in wonder as the lily flower opens to reveal an automated butterfly, slowly flapping its wings. The fairy then bows her head and returns to her repose.

Even with Junod’s expertise in automata, it took years before he could see a way to make the Van Cleef team’s vision a reality. He presented his ideas for the mechanism in matchsticks and, for the enameled leaf parts, in rubber bands and wood. ‘I love to do the prototypes, it’s a real challenge,’ he says. ‘With this project, the dimensions were new to me and required a different method. Also, we were working with two opposite types of engineering – mechanics and jewellery – and they work in different ways.’

Each part of the fairy had to be cast and worked separately by the Van Cleef & Arpels jewellery workshop, which followed Junod’s instruction that every piece of the figure had to move. ‘She’s small, so there are so many components, and she’s gold,’ he says. ‘Gold makes her very heavy, so it is hard to create a smooth movement.’ As Junod worked, so the jewellery workshop had to alter its parameters and develop techniques to respond to his every change. And there were other constraints, too: the added weight of precious stones, the trial-and-error enamelling process, and the demands of remaining true to the Van Cleef & Arpels figurative aesthetic.

The Fée Ondine automaton has been in development for more than five years. It took 20 workshops and many craftsmen more than 12,000 hours of work to create; they used 2,870 components, from gold and silver to precious stones, iron and copper. ‘The art of mechanical systems is very hard – a lot of this work is instinct and experience,’ Junod says. ‘Before the invention of transistors or electricity, we were making cameras, record players. No one learns these skills any more.’

The fairytale scene lasts just 45 seconds. By initiating its creation, Bos is paying homage to the human aspect of exceptional skill – passion. And it would take a proverbial heart of stone not to be enchanted by Fée Ondine.

As originally featured in the Precious Index, our new watches and jewellery supplement (see W*218)

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Van Cleef & Arpels website and the François Junod website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Caragh McKay is a contributing editor at Wallpaper* and was watches & jewellery director at the magazine between 2011 and 2019. Caragh’s current remit is cross-cultural and her recent stories include the curious tale of how Muhammad Ali met his poetic match in Robert Burns and how a Martin Scorsese Martin film revived a forgotten Osage art.

-

Can the film 'Peter Hujar's Day' capture the essence of the elusive artist?

Can the film 'Peter Hujar's Day' capture the essence of the elusive artist?Filmmaker Ira Sachs and actor Ben Whishaw bring Peter Hujar back to the front of the cultural consciousness

-

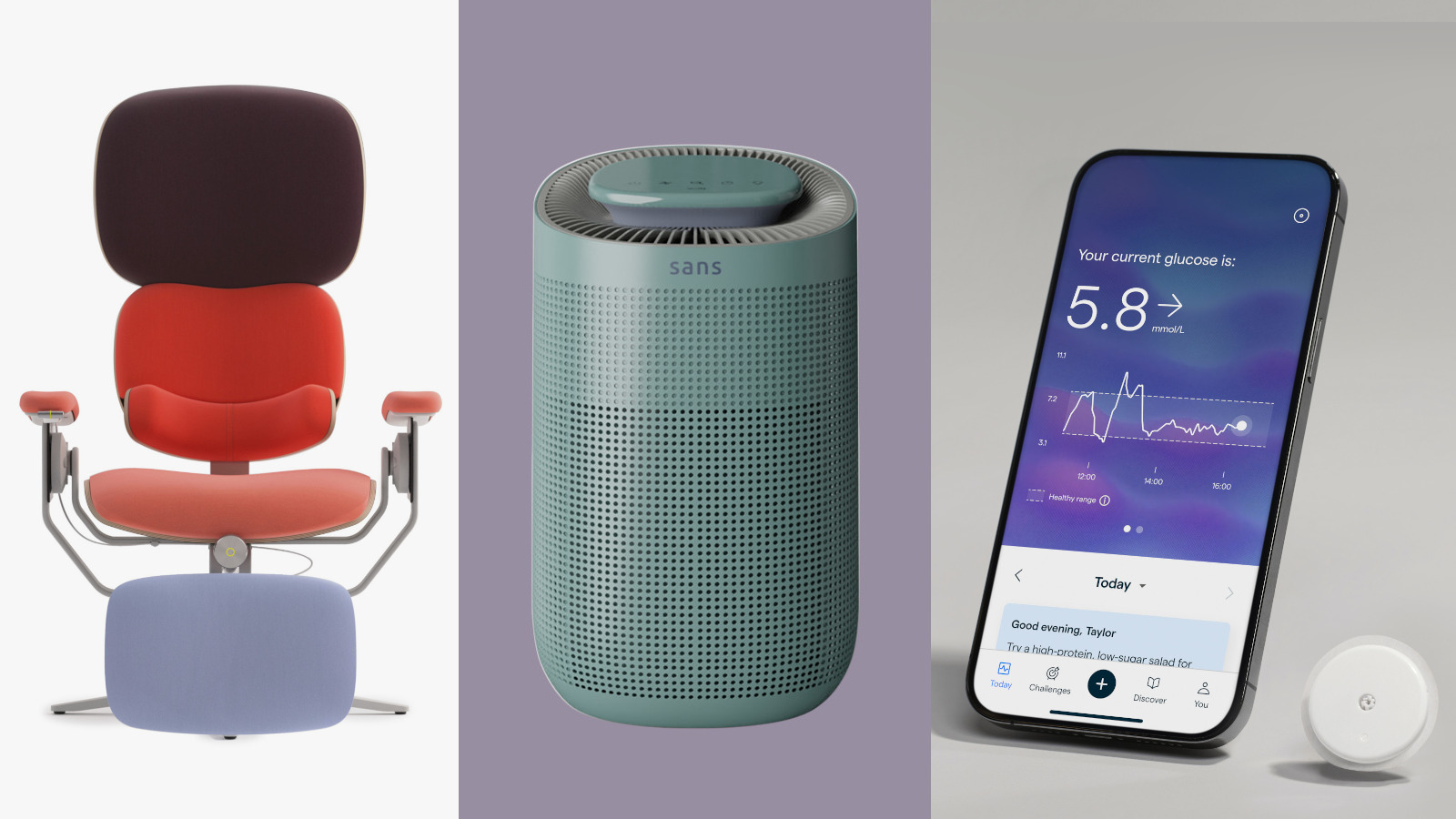

New tech dedicated to home health, personal wellness and mapping your metrics

New tech dedicated to home health, personal wellness and mapping your metricsWe round up the latest offerings in the smart health scene, from trackers for every conceivable metric from sugar to sleep, through to therapeutic furniture and ultra intelligent toothbrushes

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week'Tis the season for eating and drinking, and the Wallpaper* team embraced it wholeheartedly this week. Elsewhere: the best spot in Milan for clothing repairs and outdoor swimming in December

-

It’s time for the return of the show-stopping table clock

It’s time for the return of the show-stopping table clockA host of brands, from Piaget to Van Cleef & Arpels, are revisiting the table clock in spectacular style

-

All eyes on Greek jewellery brand Lito as it launches bold new amulets to mark its 25 years

All eyes on Greek jewellery brand Lito as it launches bold new amulets to mark its 25 yearsStriking amulets, seductive stones and secret messages characterise Lito's striking new anniversary collection, an extension of its ‘Tu es Partout’ series

-

The best layering necklaces for an elevated yet casual look

The best layering necklaces for an elevated yet casual lookHow to mix, match and stack jewellery for the ultimate high-energy, low-effort style

-

Van Cleef & Arpels light up London with the Dance Reflections festival

Van Cleef & Arpels light up London with the Dance Reflections festivalVan Cleef & Arpels are celebrating their ties with the world of choreography with the second edition of the Dance Reflections festival across London

-

Dazzling high jewellery for statement dressers

Dazzling high jewellery for statement dressersIntricate techniques, bold precious stones and designs unite in these exquisite high jewellery pieces

-

High jewellery is given a literary twist in Van Cleef & Arpels' new Treasure Island-inspired collection

High jewellery is given a literary twist in Van Cleef & Arpels' new Treasure Island-inspired collectionVan Cleef & Arpels look to Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic adventure story for a high jewellery collection in three parts

-

Take a look at the big winners of the watch world Oscars

Take a look at the big winners of the watch world OscarsThe Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève is the Oscars for the watch world – get all the news on the 2024 event here

-

An impressive private jewellery collection goes on public display in Dubai, organised by Van Cleef & Arpels’ L’École, School of Jewelry Arts

An impressive private jewellery collection goes on public display in Dubai, organised by Van Cleef & Arpels’ L’École, School of Jewelry ArtsLate French collector and antique art dealer Yves Gastou amassed an impressive ring collection, now the subject of an exhibition, ‘Men’s Rings, Yves Gastou Collection’